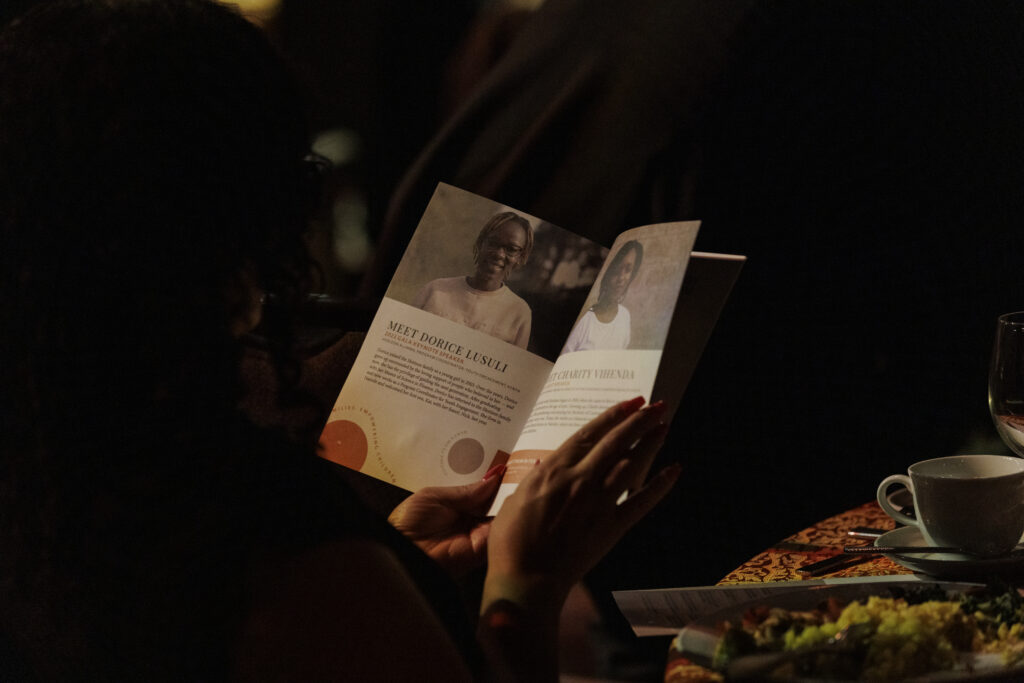

STORIES OF INSPIRATION AND EMPOWERMENT.

Welcome to the many stories and sources of inspiration of Horizon Empowers. Stories like these and the partnerships that take place can’t happen without all of us getting involved.

Programs in Action

It’s one thing to come alongside and empower children, youth and families — and another to see it all in action. Read about our programs in action!

Partnership in Action

We cannot do what we do without amazing partners who are aligned in our values and mission. Read about the exciting partnerships that are taking empowerment to a new level!

Update from Horizon Empowers

Our Horizon community is important to us. Keeping you up to date and in-the-know of what’s happening in Horizon around the world matters

Stories on Location

From the first Micro Community in Kenya, to new locations in Guatemala (2017) and Honduras (2019), Horizon has come alongside hundreds of children and at-risk youth by providing safe places to live, grow, and learn.

Kenya

GUATEMALA

HONDURAS